In response to Laura Baginski’s „Verschlingung“

by Johanna Ziebritzki

In the middle of the relief „Verschlingung“ appears a vertical center from which organic loops are swirling towards both sides where they ultimately merge with one sitting figure respectively. At the center, the rhythm of the loops is more condensed. The loops unfold their symmetry and widen their curves towards the figures. On the left side, the plaiting is coalescing with a man who sits on one leg while resting his arm on the other. Between his thumb and fingers, he holds the heel of the leg he sits on. The bent elbow appears in line with his toes and a loop is swirling up behind his back, which concludes the account of what we can see on the left side. From his crotch emerges a branch that feeds the plaiting. By being permeated by another branch, his chest is weaved into it as well. All limbs are part of the larger symmetrical rhythm. Between the two figures the plaiting unfolds further, occupying a little more space in width and height than each figure. The man is faced by a woman who sits in similar position on the other side of the net, with one leg folded underneath her pelvis while the other one, which is bent, serves as a repository for her arm. Her vulva releases a branch and just as seen with the man, another loop grows right through her chest, swirling up behind her and supporting the back of her head and shoulder. Both heads are turned towards the plaiting, revealing their full profiles. Except for the anchoring in their pelvises the plaiting does not show roots, although its loops show a strong resemblance to plants. Some of the parting branches of the crotches bear buds, foretelling the further growth of the plant-plait. The two figures face each other with open eyes, suggesting a lingering look that weaves its way through the plaiting.

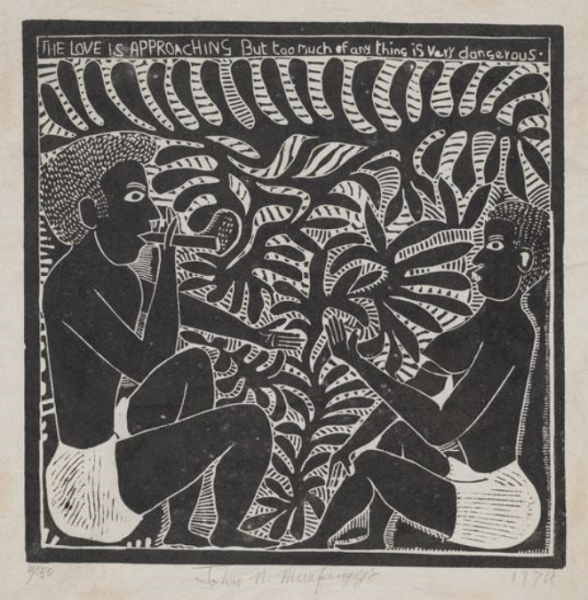

The motive of a man and a woman, bound together while kept apart by a plant-like ornamentation, appears in different contexts and times. The bronze relief „Verschlingung“ (2015 / 2018) that is described here, has been created by Laura Baginski, a sculptor and graphic artist living and working in the midst of Germany. „The Love is Approaching“ (1974) is a different adaptation of the same motive by John N. Muafangejo. In this Linocut version, the space between the two sitting figures is so small that they are almost touching each other. Their raised hands are kept apart only by a slender element of the organic ornament, which unfurls in between and above them. Muafangejo’s scene is staged under the headline „THE LOVE IS APPROACHING But too much of any thing is very dangerous“, which gives the scene a comic-esque look.

Even though Baginski’s and Muafangejo’s composition differ in technique and style, and have been created in different times and places, both realizations speak of similar experiences in regard to the longing for belonging to someone else. The figures of both versions clearly relate to one another with gestures and gazes. They are connected and exist individually, knowing of the other due to the shared space rather than immediate physical amalgamation. They are more than two, and yet are one. Both works pay tribute to this fragmentation, multiplication and extension of the own existence by means of love. They remind us of the risk to loose oneself and of love to be breath-taking if becoming „too much“. The title „Verschlingung“ of Baginski’s work encompasses several meanings which hint towards that danger. The act of gulping or being gulped is denominated by „Verschlingung“. Furthermore it comprises the German word „Schlinge“, which does evoke images of lively growing plants while also referring to a hunting tool (snare).

Yet rather than engaging with its abyssal demons, Baginski’s relief embodies a tranquil state of life affirming joy. The form given to the motive with naked, thriving bodies and the sprouting rhythm of loops testifies this state. Contrary to many contemporary artworks, the account is not site-specific, it does not pull its primary meaning from references to the environment in which it is installed. Since it gives the impression to be resting within itself, it allows being perceived by a centered approach. The possibility to evoke sense is actually restricted to the relief. Thus the production of meaning takes place within the clearly marked boundaries of the piece. This concentration enables the imagination to go into details and simultaneously lets loose by enwrapping itself in the limited whole of the carrier of meaning. The art historian and expert for Indian art, Stella Kramrisch (1896-1993), has emphasized the significance to demarcate and depict the limitations of living entities in order to act creatively. According to Kramrisch, entities are connected and differentiated only by us, by means of our meaningful perception. Thus, an immediate relation between seeing and re-creating the seen is not possible. We are making connections and differences, parting the tree from the soil, soil from our feet, our feet from our hands, and my hand of yours holding mine. Following Kramrisch’s argument further, key to creative realization is the act of outlining (darstellen), of capturing living entities as such. Through this act of determining entities, „the abundance of being” is poured in every single one of it (Kramrisch 1924, 35f.)(1). Each of the three elements of Baginski’s „Verschlingung“, man, plaiting and woman, are complete entities within themselves, while their compilation fuses them as a composition to form a conjunct entity. Baginski’s account does not offer a myriad of referential hints to the location of its presentation, current politics, theories, or modes of thinking and living gender, sexuality, family and relationships. It rather engages with the basic need to give and receive love, to be one but not to be alone, which shapes our lives, no matter when and where we live.

_________________

(1) „Es gibt keine Atmosphäre und keine Stimmung, wo ein stilles Schauen, ohne Pathos, ohne Geste in unmittelbare Beziehung zur Außenwelt tritt und in jeder ihrer Einzelheiten, die von gegenständlicher Bedeutung ist, ihr Dasein als Natur erkennt. Die Dinge sind nicht untereinander, sondern nur mit uns verbunden [...]. Allein, was das Leben umgrenzt ist wert, dargestellt zu werden; was nicht Grenze einer Lebenseinheit ist, mag nun konkret oder vorgestellt sein, läst sich schwerlich von festem Umriß umziehen und liegt jenseits künstlerischer Verwirklichung. Die Fülle des Daseins wird in die fest umrissenen Grenzen jedes einzelnen Gegenstandes gesenkt. Naturbeobachtung spielt dabei die geringste Rolle, vielmehr ist hier ein Naturfühlen am Werk, das vom Drängen des Blutes weiß, daß der Saft in den Bäumen auch nicht viel anders sein kann.“ (Stella Kramrisch: Grundzüge der Indischen Kunst. Hellerau bei Dresden: Avalun Verlag, 1924. S. 35/6)

Picture:

John Muafangejo: The Love is Approaching, But too much of any thing is dangerous , 1974, Linocut, 49 x 46cm.